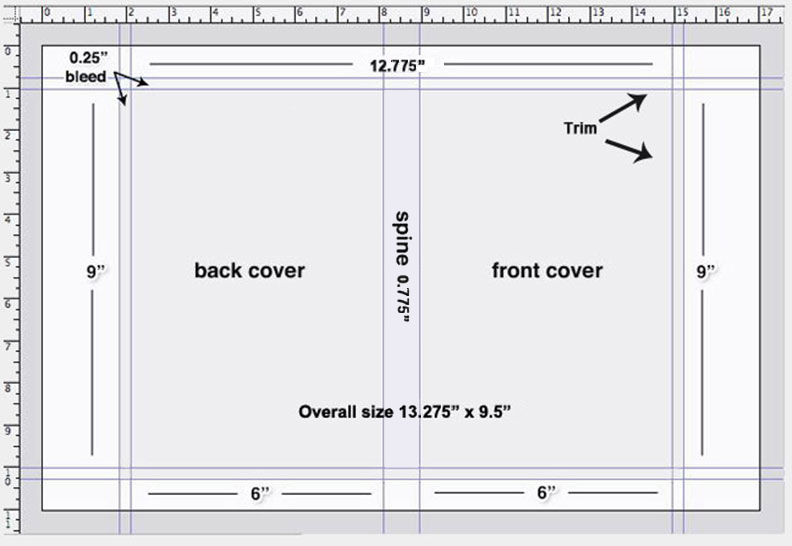

Cover Layout

-

All Images or artwork must be submitted in CMYK format at 300 DPI resolution. In many cases, the best resolution for printing is 300 PPI. At 300 pixels per inch (which roughly translates to 300 DPI, or dots per inch, on a printing press), an image will appear sharp and crisp. These are considered to be high resolution, or high-res, images.

-

When you lay out the cover of a book in a desktop application, make sure that the front and back covers, as well as the spine are designed as one contiguous page.

Example: A cover for a 360 page 6x9 book based on our 50lb paper.

Click here to download PhotoShop template

-

Bleed: Any background color or photograph that extends to the edge of the page after trimming is called a bleed. To ensure ink coverage to the bleed edge, the image or background color must extend .25 inch beyond the trim. This area will be trimmed away after printing. Neither trim nor registration marks should be placed inside the bleed area.

-

Spine Width: To determine the book's spine size, divide the number of pages by the paper's thickness (measured in "pages per inch" or ppi). Our 50lb paper is 512 ppi, our 60lb paper is 465 ppi, our 70lb is 385 ppi our 80lb is 328 ppi. and our 100lb is 286 ppi (Example: 256 page book printed on 60lb would be 256 ÷ 465 = 0.55" spine.) For "safety", provide at least .0625" tolerance within the text on the spine. There can be no printing on a spine that is less than 0.25" (1/4").

-

Other papers:

-

70lb Warm White is 377 ppi

-

80lb Gloss Book = .0039 Caliper @ 512 ppi

-

80lb Matte Book = .0046 Caliper @ 434 ppi

-

100lb Gloss Book = .0047 Caliper @ 426 ppi

- 100lb Matte Book = .0061 Caliper @ 328 ppi

Click here to download our Spine calculator

-

Spine Width and Variance: It is important to keep in mind that each book printed at Keystone is individually printed and bound. Therefore you should avoid hard vertical lines separating your front or back cover panels from your spine and should allow for at least a 0.125" variance of your spine on each side (for example, the text on a 1" spine should be no larger than 0.75" wide).

-

Color Breaks on the Spine: This involves a spine whose color is different from the color used on the front or back cover. We call this a "color break." Because the bulking of paper can vary slightly, it is inadvisable to create a color break between the spine and both the front and back covers. It is better to have only one color break, either on the front or the back.

Another solution is to extend the spine color over onto the front and/or back cover by about 1/4 inch. -

For best results text should be at least 0.25" from trim edges of the book.

-

If scanning to create the digital file, scan all images at 300 dpi CMYK.

-

Black elements should NOT be built in "Registration" black. These elements should be built out of "Rich" black. For best results, we recommend the CMYK values of 60% Cyan, 40% Magenta, 40% Yellow, and 100% Black. CMYK total value should not exceed 240%.

-

The barcode should be built in 100% Black only.

-

File Types Accepted:

PSD, TIFF, JPEG, PDF, PNG and EPS

This paper has a pleasing warm white color. Natural tone papers are considered to be easier on the eyes than bright white papers, and are frequently used for poetry books, novels, and any other text based book which does not contain many, if any images. Color images will not print accurately on this stock as the paper base is not a true white. We stock this paper in 50lb and 60lb text weight, though lighter weights are available for books with high page counts.

This paper has a pleasing warm white color. Natural tone papers are considered to be easier on the eyes than bright white papers, and are frequently used for poetry books, novels, and any other text based book which does not contain many, if any images. Color images will not print accurately on this stock as the paper base is not a true white. We stock this paper in 50lb and 60lb text weight, though lighter weights are available for books with high page counts.